Lost streams of Washington, D.C.

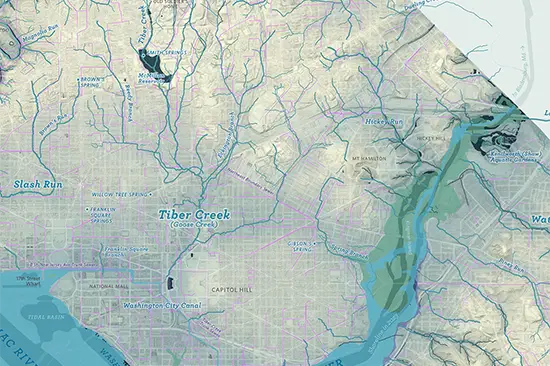

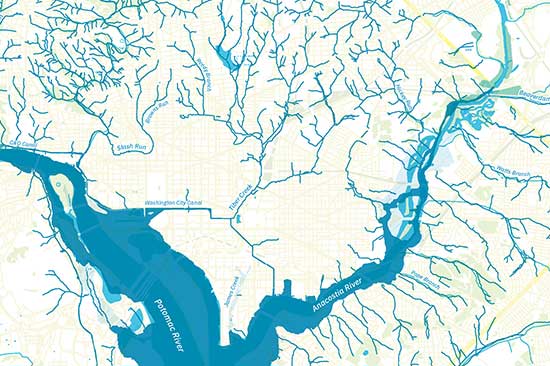

Streams, shorelines, marshes, and canals of Washington, D.C. in the early–mid 19th century. (Larger version, and more about this map.)

Mapping the city’s historic hydrology

I’m interested in water issues and historical land use in Washington, D.C. Working from old maps and reports, I’m making maps that show the course of long-lost streams and forgotten shorelines. I lead landscape history tours of DC, exploring underappreciated aspects of the city’s growth.

Maps

A wetland in front of the new Lincoln Memorial, 1917. (National Photo Company collection, via the Library of Congress.)

The buried streams project for DC DOEE

For a comprehensive view of DC’s historic hydrology, see Uncovering the History of the District’s Buried Streams, a website by Straughan Environmental and the Department of Energy & Environment. (I helped with research, writing, and design.) The site offers digitized versions of old maps, and photos, illustrations, and newspaper stories about the city’s waterways. There are also explanations about groundwater and stream restoration, and a study of sites for future daylighting projects.

Press and events

- Lost Streams of D.C.: Lower Rock Creek, A Bike Tour, June 2025

- Panel, “Waterscapes of Enslavement and Freedom: Towards a Hydrography of Race and Placemaking in Antebellum District of Columbia,” DC History Conference, April 2025

- Lost Streams of D.C.: Slash Run, A Walking Tour, Dec. 2024

- Interview on I Hate Politics (June 5, 2024)

- Native Plants & the Waters of Friendship Heights (Friendship Heights Alliance, June 2024)

- Streams map in 730DC (March 29, 2024)

- The lost streams datasets are featured in The nation’s capital, built on water, struggles to keep from drowning (Washington Post, December 19, 2023)

- “Shining ‘daylight’ on the Chesapeake Bay’s buried streams”

(Chesapeake Bay Journal, July 2023) - “D.C.’s unique history provides a bit of extra security from sea level rise”

(NPR Weekend Edition, Aug. 2022) - Talk, CHRS Preservation Cafe: Buried Streams, Capitol Hill Restoration Society, Jan. 2022

- Lost Streams of D.C.: A Preview Bike Tour, Nov. 2021

- “70% Of D.C.’s Streams Have Disappeared. Where Did They Go?”

(WAMU, Aug. 2021) - D.C.’s Hidden Waterways with Urban Adventure Squad, spring 2019

Background

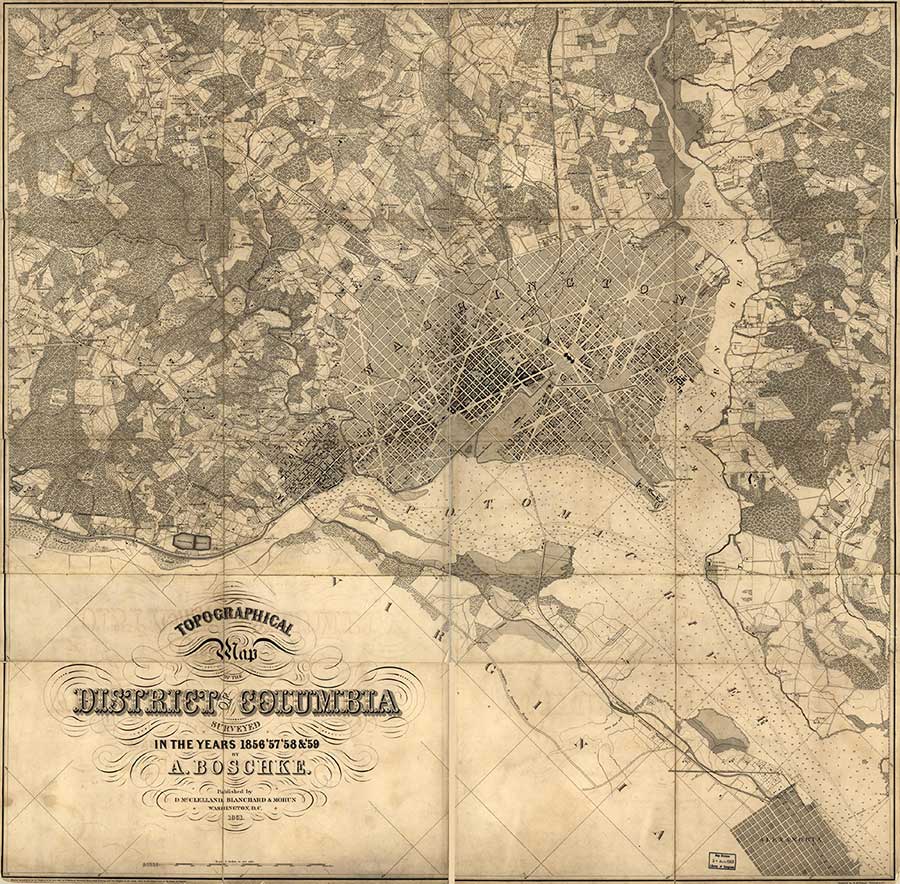

Boschke map, 1861, from the Library of Congress.

Tiber Creek and Slash Run

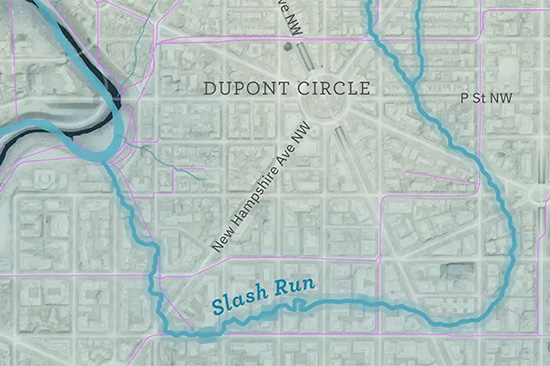

Here’s the hydrographic environment in 1859: Tiber Creek is the largest of the lost streams, draining much of the city. It ran from a spring in the present-day McMillan Reservoir down through Union Station—Swampoodle—and past the Capitol Building. At the Mall, Tiber Creek merged into the ill-fated Washington City Canal and debouched into the Potomac’s wide tidal. There was a large public wharf at the end of the canal, along 17th St. below the White House. Slash Run (now the namesake for a burger joint) flowed from Adams Morgan down through Dupont.

James Creek

James Creek ran from near the James Creek Marina up to Eye St. SW. It split the southwest waterfront in two, dividing Buzzards Point from Greenleaf Point. The creek might have flowed more freely at the time of the city’s founding, but by 1859 it was already a marsh.

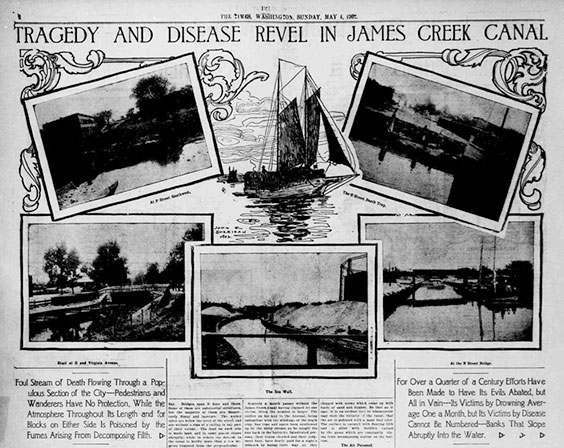

“Tragedy and Disease Revel in James Creek Canal,” Washington Times, 4 May 1902. (PDF at Library of Congress.)

In the 1870s, a city project turned the marsh into a canal, host to schooners and barges delivering lumber and sand to the surrounding industries. Pedestrians fell down the canal’s sloping sides and drowned, and the slow-moving waters spread foul air over the neighborhood.

Southwest Waterfront

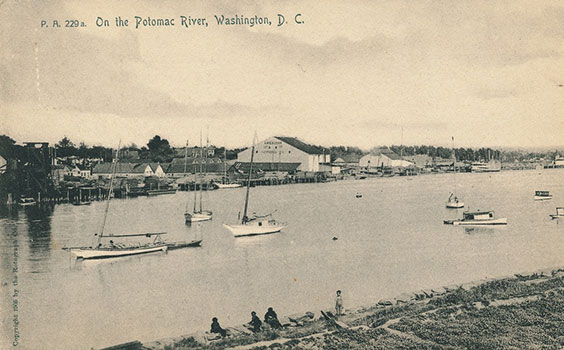

Southwest Waterfront, 1905 postcard.

The Potomac River waterfront, downstream of the 14th St. bridges, served steamer traffic to the rest of the Chesapeake Bay. The Municipal Fish Market was located there, as well. When the market’s buildings were razed in the 1960s, the vendors moved to boats and barges moored along the wharf.

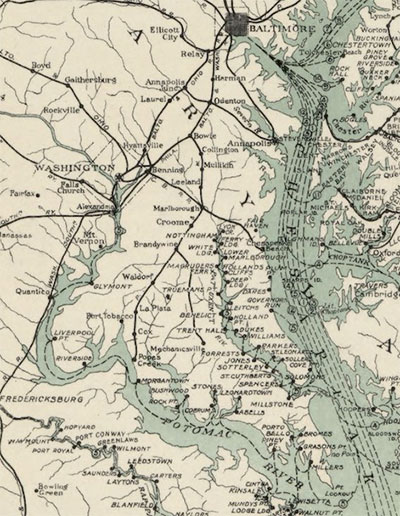

Chesapeake Bay steamboat lines. Map by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 1926.

Marshes

West of the Mall, much of the Potomac was tidal flats, mud at low tide. East Potomac Park on Hains Point was created by Corps of Engineers dredging work in the first decade of the 20th century.

Marsh grasses. Parts of the Anacostia would have looked something like this in 1859. These grasses are elsewhere, but today, there are a growing number of healthy marshes along the Anacostia.

Similarly, there are large expanses of marshland along the Anacostia—not bare mudflats, but wetlands that were host to semiaquatic vegetation. That slow-flowing river was already beginning to clog with sediment washed down from Maryland farms. The Anacostia’s modern shoreline is also mostly the result of 20th century dredging and landfilling.