D.C.’s private waterfront land —

Along the Potomac

Written for Greater Greater Washington’s “Water Week” and published on that site in two parts, for the Potomac and for the Anacostia.

This post is part 1 in a miniseries for GGWater Week exploring privately owned waterfront property on the rivers that define much of DC. First up, we explore the properties adjacent to the Potomac River.

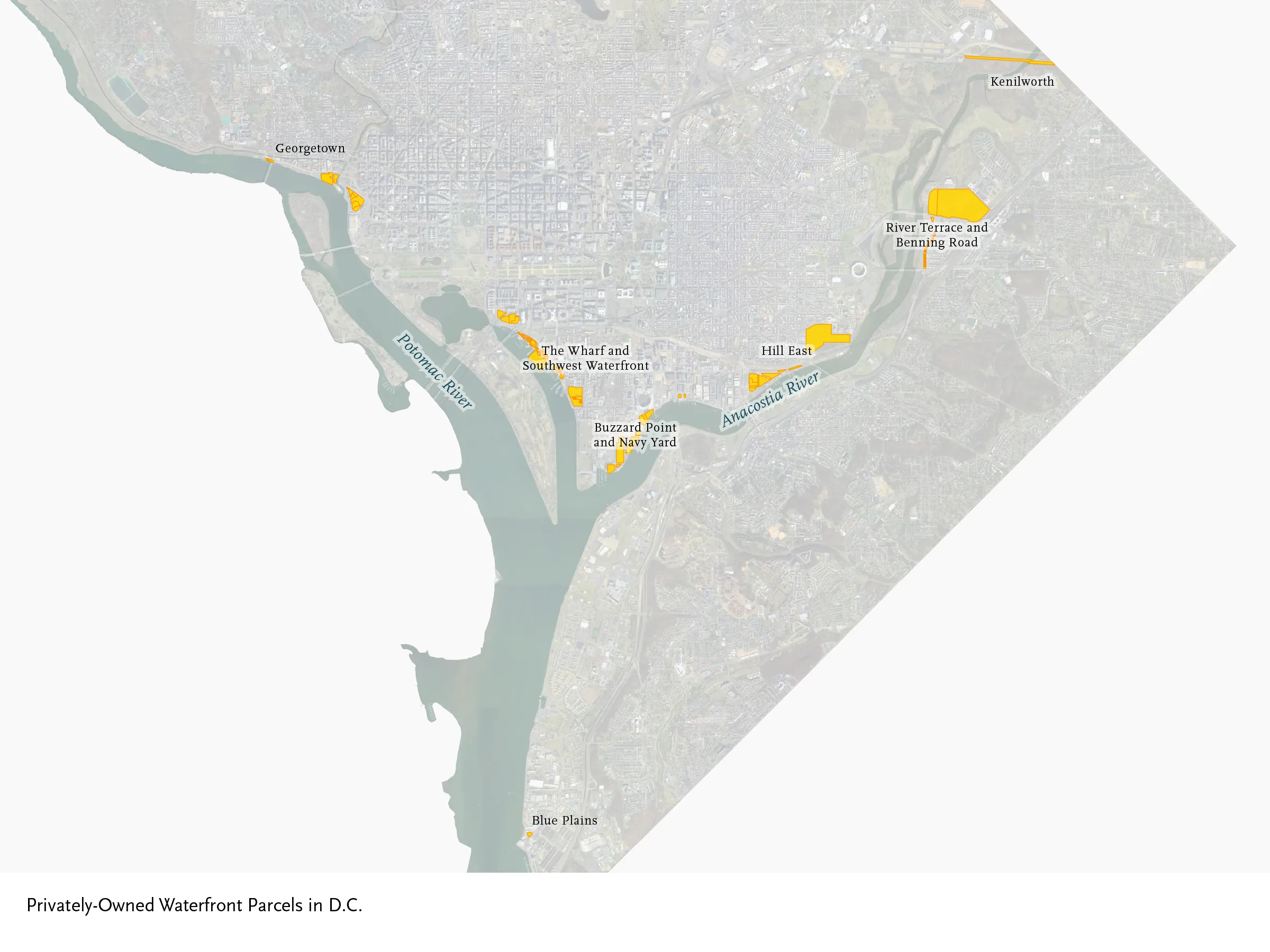

DC sits at the confluence of two rivers, on a site chosen for its easy access to tidewater. Yet almost all of the waterfront land in the city is owned by the federal or DC governments. The District’s Common Ownership Lots dataset contains 137,375 entries, for every category of lot. Only about 180 of them are privately-owned and on the water, for a broad definition of “waterfront property” that includes both the lots that touch the river and land that has a clear line of sight to the river across narrow parks. This pair of articles maps all of those few, privately-held lots, and offers photos of the most interesting ones. Let’s start with those properties facing the Potomac River.

Boathouses and Prized Addresses:

Georgetown and Foggy Bottom

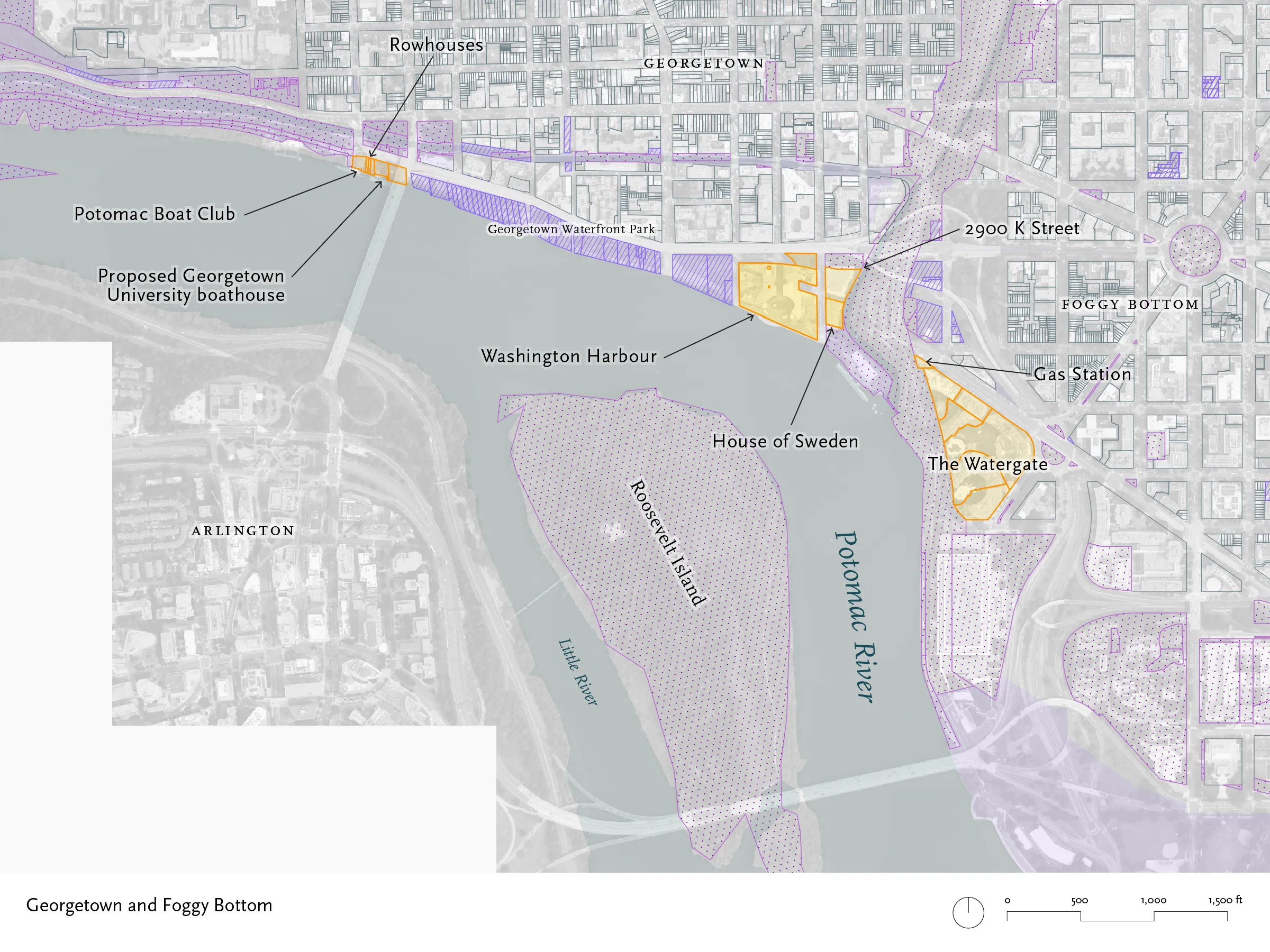

This area was once a working waterfront, served by the B&O Railroad’s Georgetown Branch, by wharves that could accommodate barge traffic, and by the C&O Canal, til its closure in 1924. The last industrial operations left in the 1980s, and the site of the railroad yards and team tracks is now Georgetown Waterfront Park, owned by the District. There are now three groups of privately-owned lots above the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge, all in commercial, residential, and recreational use.

Farthest upriver is the Potomac Boat Club, a rowing organization with a boathouse tucked next to the remains of the Aqueduct Bridge.

Just downstream of the boathouse are three rowhouses. There are only a handful of single-family homes facing the river. Next to them (at left in this photo) sits the open lot used by the Key Bridge Boathouse, a boat rental facility run by Boating in DC, under a concessions agreement with the National Park Service.

Key Bridge Boathouse operates on land that was long held by the National Park Service, but which has now been transferred to Georgetown University. Earlier this year, the university, the National Park Service, and the District government announced a three-way land swap. Georgetown gained ownership of the lots next to the Key Bridge, and the institution plans to build a boathouse there. They moved quickly, and presented design concepts to the Old Georgetown Board in July. It is not clear when or where the public boathouse will reopen.

This spot has been the site of a rental boathouse for eighty years — Jack’s Boathouse from 1945 til 2013. Jack’s retained ownership of one tiny, 240 square foot parcel, hemmed in by parkland, until Georgetown bought that property back in July.

Below Georgetown Waterfront Park are two high-end commercial office buildings, home to law firms, restaurants, and diplomatic missions. Washington Harbor was designed by Arthur Cotton Moore and completed in 1986. The House of Sweden dates to 2006. Flooding, from heavy rains up the Potomac or by hurricane-driven storm surges, presents a threat to all of these sites. Washington Harbour is protected by portable flood walls, although in 2011, crews failed to raise the barriers and the building was inundated. The first floor of the House of Sweden is raised above street level.

Below the mouth of Rock Creek and the remains of the C&O Canal’s tide lock is the Watergate. Though separated from the river by a highway and parkland, it enjoys waterfront views. One triangular lot houses a 1932 gas station famed for its high fuel prices.

Midcentury and the 2010s:

The Wharf and Southwest Waterfront

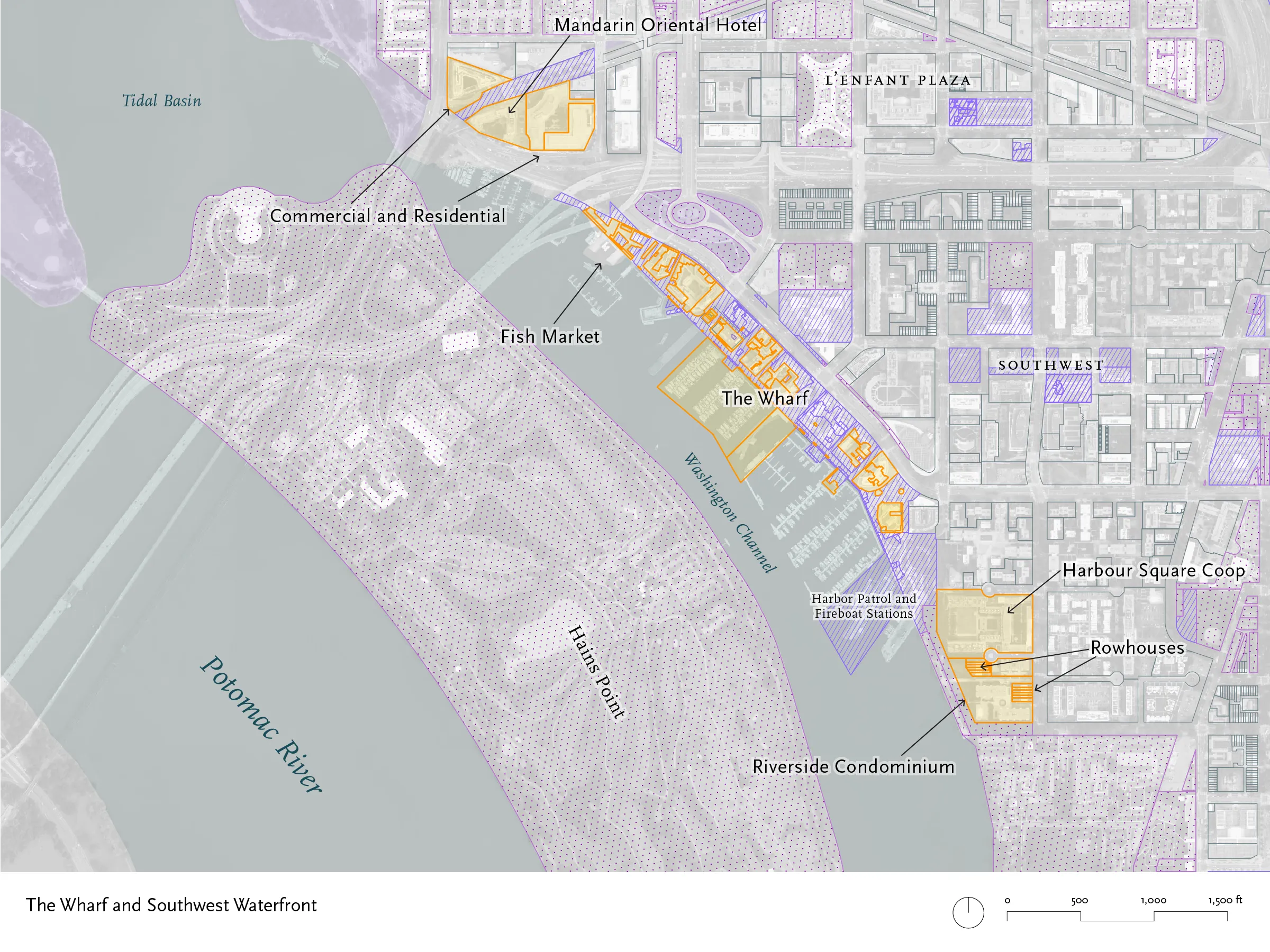

The Washington Channel was the deepwater branch of the Potomac, and the Seventh Street Wharf served as the city’s main steamboat landing from the 19th century through the end of the Chesapeake Bay packet lines. The area saw a wave of urban renewal projects in the 1960s, which left it with midcentury residential buildings and concrete parks. The current development program began in 2003, with construction starting in 2014.

Two remnants of the old Municipal Fish Market survive: the Oyster Picking Shed and Lunchroom, designed by Snowden Ashford and completed in 1918, now houses the Rappahannock Oyster Co.

Jesse Taylor Seafood is the one remaining fish market vendor, still selling from floating barges. The High Water Mark sculpture, by Curry Hackett and Patrick McDonough, indicates the heights of the record floods from 1920 to 2010.

Buildings at the Wharf sit on platforms, elevated above the normal high tide line. There are at least half a dozen levels—floating docks to allow access to boats, layers of low wharves toward the water, the promenade, and raised “porches” in front of each of the buildings. The Wharf is legally complex, too, with dozens of overlapping lots, some of them drawn so that they follow the curves of buildings.

Just to the south of the Wharf is a park designed by Sasaki Associates in the 1960s, flanked by condo and coop buildings and by a handful of townhouses.

This area has long been cut off from the District — first by railroads and canals, then by highways — and the streets just south of the Wharf are still quiet.

In the second post of this mini-series later this week, we’ll explore the privately owned properties on DC’s Anacostia riverfront.