GDES-360 spring 2021 / David Ramos, American University Design

Encoding data

We’ll start by exploring ways of encoding data in visual form. For this first project, represent 72 hours of weather observations from Washington/Reagan National Airport (KDCA), as a graphic.

Come up with two systems for picturing the data:

- A system that is as clear as possible.

- A system that is more expressive, but might not read as reliably.

This method of developing more than one approach—prompting you to make one version that works well and another that is more daring—will reappear over the semester.

There are conventions and widely recognized techniques for encoding data. We will look at them, in time. You can look at some of the systems for graphically representing weather, quite clever and fascinating ones, if you would like, but the main lessons for this project come from creating your own.

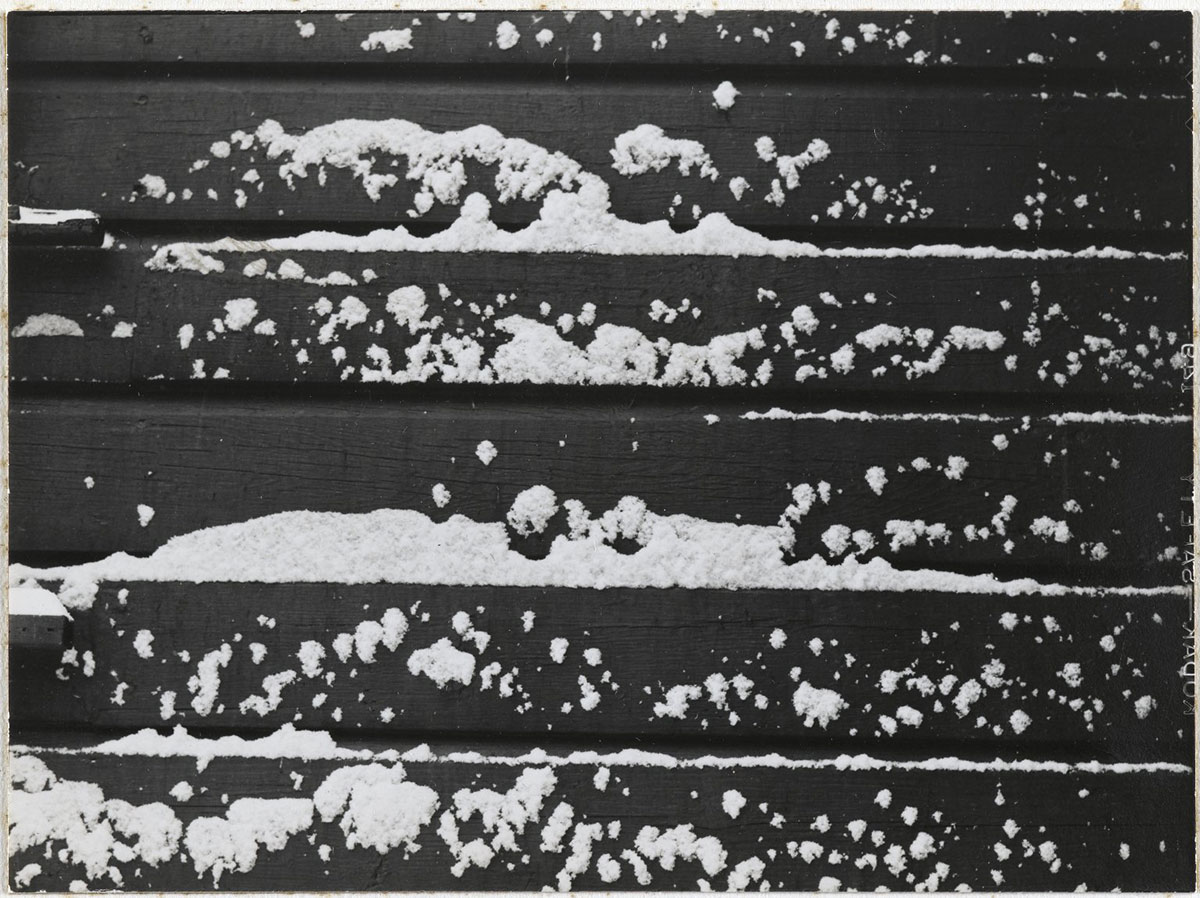

"[Untitled] (Snow on Clapboard)," by Consuelo Kanaga. Image: Brooklyn Museum, CC BY (original).

Specifications

Format: Present this on paper. For reading distance, assume that the graphic might be laid out on a table or posted on a wall. Do have this printed before class if at all possible.

Size: Each graphic can occupy up to 50 square inches. (A 1×50 in. graphic would work. So would a 5×10 in. graphic. Or a 3×3 in, though that would be a particular challenge.) Your two systems can be different sizes.

Color: Your choice. Personally, I’d find black and white easiest.

Production method: Your choice. Consider doing this by hand, at least for sketching out ideas and possibly for the final piece. (Tip: you can draw this at a larger size, then scale down the visualization to final size by scanning or photocopying.)

You should almost certainly provide some text labels, and you can choose to include a key.

Design for an audience of high-school educated adults who do not work with weather data, but are curious.

Your data!

Washington/Reagan National Airport (KDCA) data are available through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/National Weather Service websites. You can work with the most recent 72 hours of data, if you like, but save the file because the data are continuously changing.

We might get a storm over the weekend, but if you’d prefer a little guaranteed drama, you can work with data that I saved at 9:53 a.m. on Wednesday, (ZIP archive w. PDF and HTML) catching the snow.

Choices and explanations

The three-day data include 72 hourly observations. You might present all 72, or you could look at every two, three, four, or six hours.

There are headings for over a dozen variables. Choose three. The “weather” and “sky conditions” columns contain non-numerical data, but you can absolutely choose to work with them. You can also choose to show trends in variables.

Sky condition is the cloud coverage, in METAR code. The entry BKN050 means broken clouds at 5,000 feet. For translating METAR, see an explanation archived from Weather Underground) or the Wikipedia article.

The data include entries for date and time. They don’t count toward your three variables. You’re going to be presenting data at regular intervals. Try to find a solution that doesn’t require repeating the time across the entire visualization.

We’re working with a particular 72 hours, but ideally, the system could cope with a whole range of data.

Your big choice, of course, is how to encode these data. It’ll be exciting to see what you come up with.