Etaoin Shrdlu

Etaoin Shrdlu: a series of letters, either the most common letters in English or a run of nonsense text, depending on context

Codes and ciphers

“Cryptanalysis rests upon the fact that the letters of language have ‘personalities’ of their own,” writes David Kahn in his history of cryptography.1 Cryptographers – the people concerned with the making and breaking of codes – know that certain letters appear more often than others. ETAOIN SHRDLU approximates the frequency of letters in English text. E is the most common, followed by T, A, and O in that order, and so on.2

All the News Thats Fit to Pritn

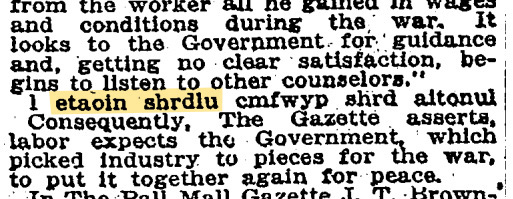

Etaoin Shrdlu gains its limited notoriety not from the hidden world of cryptography, though, but from journalism. Here’s a 6 Feb. 1919 New York Times article about strikes in Europe:

See the highlighted words (the highlight is mine)? It’s our friend Etaoin Shrdlu!

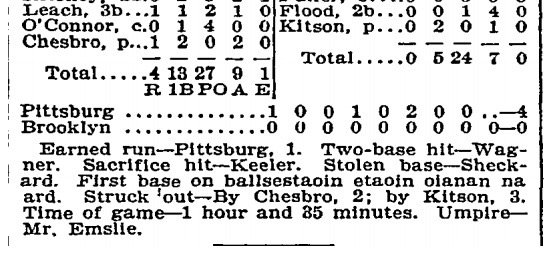

This odd phrase appears elsewhere. These box scores come from the Times’ 5 July 1902 edition:

In fact, there are dozens more examples in the Times archives, if you wish to look.

How did a representation of the most common letters in English find its way into an article? As in so many cases, we can blame a typographical error.

Say it in hot metal

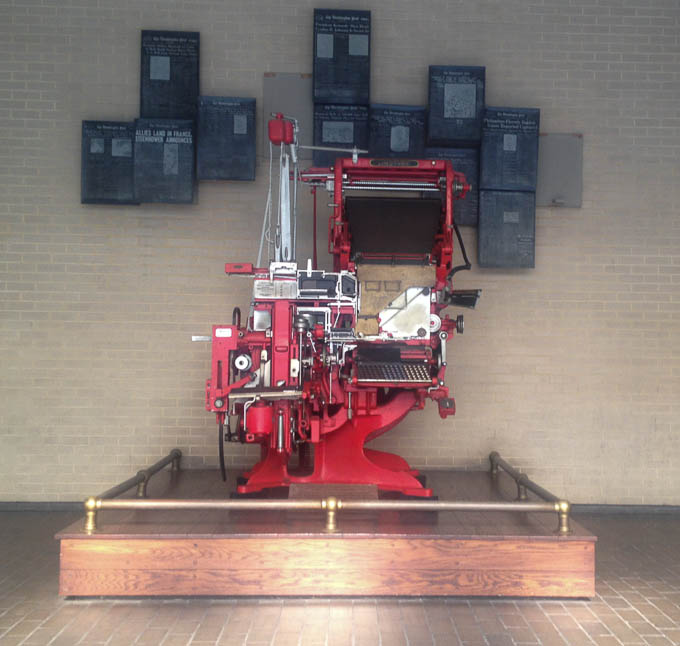

Linotype machine on display at the main entrance to the Washington Post.

Before computer-driven page layout or the brief flash of photo-optical composition, newspapers printed their issues using metal type. Operators would take stories in handwritten or typewritten form and re-key them on refrigerator-sized machines that spat out lines of metal type, ready to be arranged into layouts.

The Linotype – the most popular typesetting machine in the newspaper business – used a special keyboard layout that placed the most commonly-used lowercase characters on the left side, with CAPS on the right.

Keyboard on the Post’s Linotype.

When Linotype operators made mistakes, they could run their fingers down the rows of keys to fill out the rest of the line, much as a person on a computer might type out “askdjgadkls;lfj” in a moment of pique. (You can watch Linotype operators explain in a clip from Linotype: The Film.) Usually, further along in the production process, the compositor would recognize the nonsense text and throw the lines out.

Sometimes the compositors and editors missed “etaoin shrdlu” and dropped the gibberish into a story.

Sometimes these strings of nonsense make their way into a newspaper archive, where they are preserved and searchable online.

This run of letters gives its name to the documentary film Farewell, Etaoin Shrdlu, about the last day of Linotype operations at the New York Times in 1978. The two filmmakers, David Weiss and Carl Schlesinger, both worked at the Times. I have a vague memory of seeing the film in a class ten or fifteen years ago, probably watching it on a dusty 16 mm projector.