Original syllabus

GDES-396 spring 2020 (David Ramos, American University Design)

ramos@american.edu · office hours

This is the syllabus as originally written, for a face-to-face course, as of January 15, 2020.

Three-dimensional chart used by Central Electricity Generating Board planners, c.1954. Photo: Science Museum Group, CC BY-NC-SA.

Data Visualization and Information Design

This course examines the design of data visualizations, information graphics, and maps. Through creative projects and exercises, students explore techniques for displaying quantitative and spatial data, explaining complex systems, and shaping numbers into stories. Combines studio practice with reading, technical demonstrations, and supporting lectures.

Learning outcomes

You will learn to:

- Reason about and visually explore quantitative data

- Design graphical displays of quantitative information

- Present spatial data on maps

- Employ type, color, and shape in visualizations

- Evaluate visualizations for candor and effectiveness

- Identify the strengths, limitations, and assumptions of datasets

- Use spreadsheets and statistical software for data processing and analysis

- Produce visualizations using statistical and drawing software

- Work with GIS tools

- Translate real-world questions or intellectual inquiries into quantitative frameworks

- Select and apply appropriate quantitative methods or reasoning

- Draw appropriate insights from the application of a quantitative framework

- Explain quantitative reasoning and insights using appropriate forms of representation so that others could replicate the findings

Structure

This is a project-based course. Class meetings will include a mix of demonstrations, discussion, critiques, and studio working sessions. Expect to be doing most of your design work outside of class time.

You might notice that we have shorter class meetings than other AU design courses. Class time focuses on critical, conceptual, and formal issues, and on refining the skills that you initially learned outside of class. Most of details of technical, software issues, you will need to learn from the reading. In-class demonstrations and lectures focus on tying together the reading and on offering insights that aren’t readily available offline.

This course is organized so that students from a wide range of backgrounds can flourish in it. If you say don’t like math, that’s fine, but you have to be interested in thinking about numbers. If you haven’t yet worked with typography and graphic design, that’s also fine, but you have to be willing to learn. No matter your background, though, you need to be curious about a broad array of questions and problems out in the world, and able to explore those issues through quantitative data. This class is about design, not about getting software to do something; you’ll need to be excited about going farther than the defaults.

Humanities Truck project and participatory design

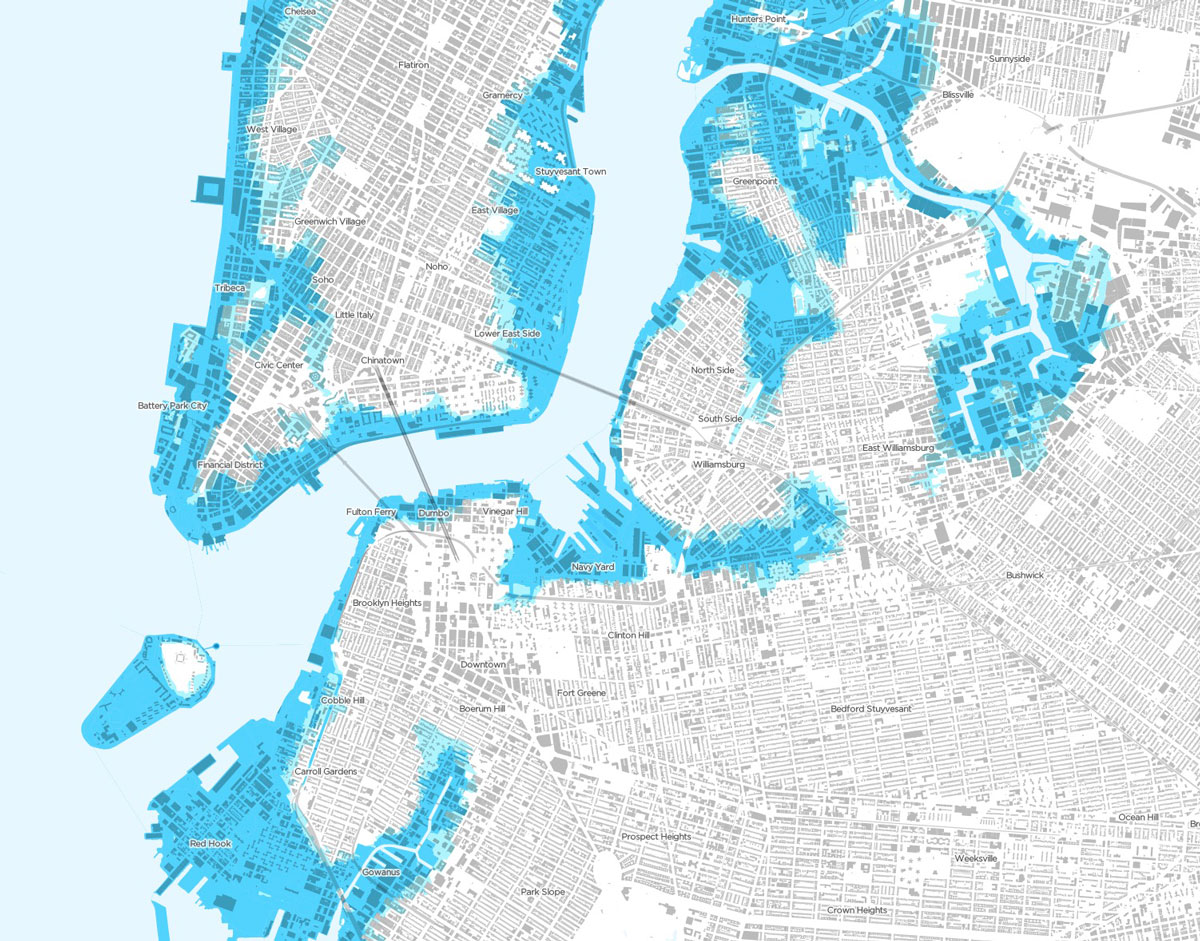

This year, I’m running a project, Before the flood, through the AU Humanities Truck. The project asks how will DC change in response to the climate crisis? Design can help us have more ground, equitable conversations about the choices we must make. You’ll have the option of adding your work to the interactive programs and exhibit.

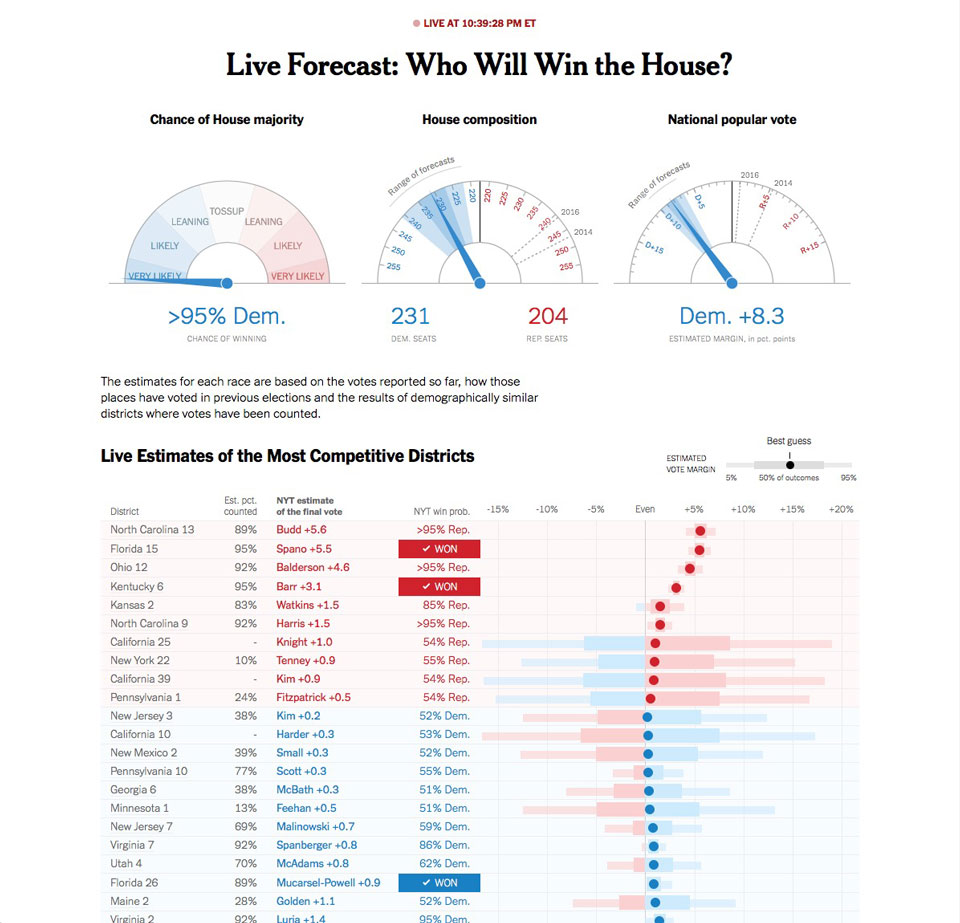

Election results page, designed to convey uncertainty about the final outcomes. New York Times, 6 November 2018 at 10:39 p.m.

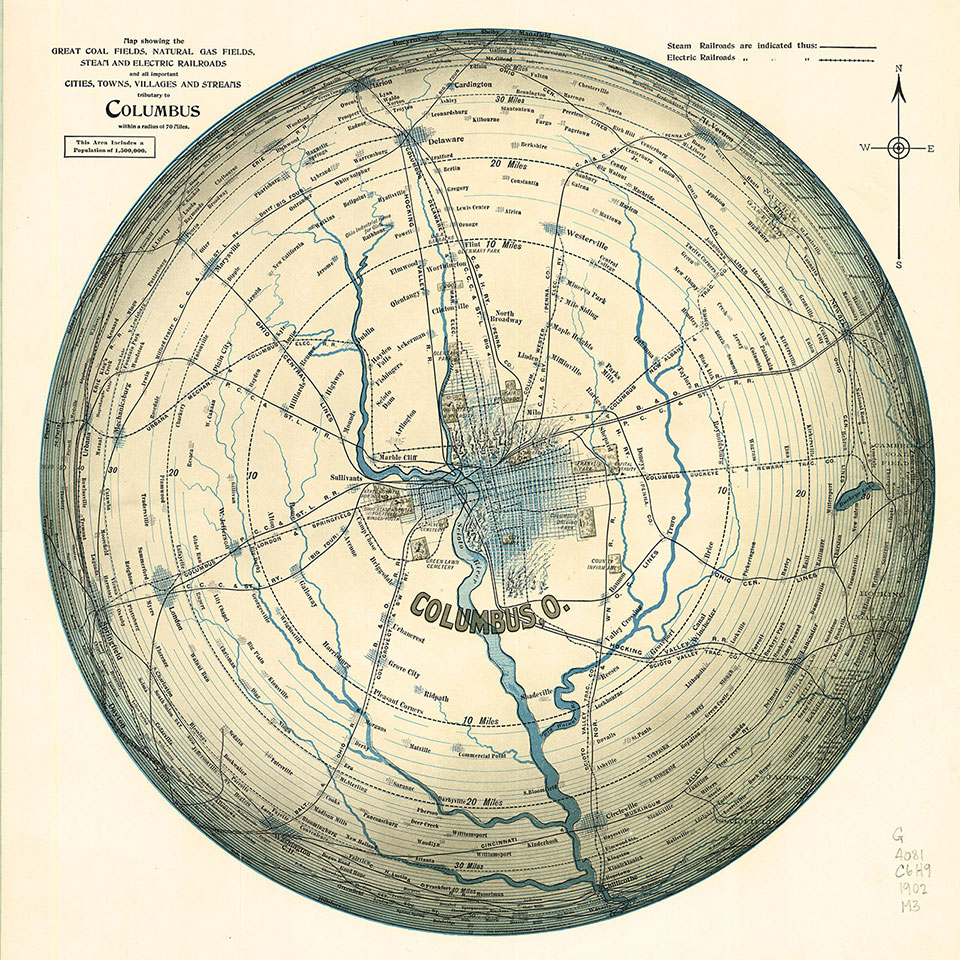

Map of the area 70 miles away from Columbus, Ohio, 1902. Courtesy of UConn Library, CC BY-NC. (original.)

Tools and resources

Reading materials

There is one required textbook, along with assigned reading from other sources.

Cairo, Alberto. The Truthful Art: Data, Charts, and Maps for Communication. Hoboken, N.J.: Pearson Education, 2016. ISBN-13: 978-0321934079. author’s site

The book is in course reserves at Bender Library, and is also available in electronic form through the library.

Additional resources

The AU Library provides access to Lynda.com online tutorials. We will be relying heavily on video tutorials for covering technical topics.

Software

We will be reading about and working with certain tools in class:

- RAWGraphs (free)

- Flourish (free)

- Workbench (free)

- Adobe Illustrator for editing vector graphics and for some simple charting. Illustrator is installed on lab machines, and Adobe offers education pricing.

- A spreadsheet program. Excel, Numbers.app, Google Sheets, and OpenOffice are all fine.

- R and RStudio, free or open source, and installed on lab machines.

- QGIS, a free/open source GIS, available on lab machines.

- Possibly, Mapbox, a software-as-a-service product. The free accounts will serve you well.

This course assumes that you have a working knowledge of Illustrator or an equivalent vector graphics program, or that you can learn through tutorials. If you would like to do projects in another vector drawing program, like Inkscape or Sketch, those programs might work, but you should not expect help with them.

Supplies

You’ll need some other supplies:

- Paper or sketchbook, for sketching and for taking notes

- Technical pens, drawing pencils, and markers (please don’t struggle through sketching with a ballpoint pen)

- Colored pencils or colored markers, at least a few

- Straightedge or ruler

- Tracing paper

- Graph paper (or a printout of graph paper)

- USB thumb drive, portable hard drive, or cloud storage account

- A separate drive or account for backup

Good places to purchase:

- Sullivan’s Art Supplies, 4200 Wisconsin Ave. NW, Washington, DC (Tenleytown—limited selection)

- Plaza Artist Materials, 1990 K St. NW, Washington, DC (Metro to Farragut North; N busses from Ward Circle)

- Plaza Artist Materials, 7825 Old Georgetown Rd., Bethesda, MD (Metro to Bethesda)

- Dick Blick Art Supplies, 1250 I St. NW, Washington, DC (Metro to McPherson Square or Metro Center)

New York City floodplains. Data from NYC OpenData. Map by the instructor.

Policies and expectations

Projects and grading

The course schedule, assignments, and these percentages may change.

- 45–50% Intro projects

- 45–50% Large projects

- 0–10% Quizzes

- Participation modifies grade as necessary

Process and due dates

Projects in this class build through iterations; start early and work consistently. You will need to turn in evidence of your process, so keep versions of your files and paper sketches as they progress. Projects not seen in progress during previous classes will receive a failing grade.

Projects are due at the beginning of class, if you want to stay on schedule. You may turn in or resubmit projects through the last day of class without penalty.

See instructions for submitting work.

Grading scale

- A (excellent) Work that is clearly superior.

- B (good) Work that reflects a strong understanding of the material.

- C (fair) Work that shows basic competence and fulfills the requirements of the assignment.

- D (poor) Work that is unsatisfactory or inadequate.

- F (failing) This grade is assigned for failure to complete work in a timely and competent manner, or for non-attendance.

Attendance and the classroom

Come to class, on time. It is better to show up late than not to arrive at all. You can miss one class, for any reason, without penalty. Additional absences or missed class time will count against your course grade; final grades drop by 4% for each unexcused absence.

Grounds for excused absences are illness, religious observances, family emergencies, and military or jury service. You do not need to provide a note, but you must let me know by email.

In the classroom, conduct yourself professionally, in a way that shows respect for your fellow students, your instructor, and the material. Do not record audio or video; if you need a recording, your instructor will arrange for one.

Citations and academic integrity

You’ll need to provide citations for every piece of work that you didn’t make yourself. This includes text, images, ideas, and code. It includes images that you edited, images that you traced, and even images that you merely used as references for your own illustrations.

When you turn in the files for a project, include a list of citations in a separate document. You need not adhere to any particular citation format (though consider the Chicago Manual of Style). Whatever you do, your instructor must be able to identify the material and find the original. If you have a web address, provide it.

An example citation:

My drawing of a bird is traced from a freely licensed

photo by John Cobb, on Unsplash.

https://unsplash.com/photos/mk2USqDQE5E

Try making your own images and photographs. You will learn more, and the results are likely to be more original.

Standards of academic conduct are set forth in the university’s Academic Integrity Code. See your instructor if you have questions about academic violations described in the code, as they apply in this course.

Support services

American University offers an array of support services.